“The misconducts of this puny river Kosi can’t be tolerated any more. We have to control and tame it now.” Said JL Nehru the first prime minister of India after an arial survey of the flood effected regions of Saharsa (Bihar) on 20th of August 1951. Thus started the work on Kosi barrage in the Belka hills region. It was decided that soil would be used to create embankments from the hills so that a barrage can be made in Bhimnagar (where Kosi enters India). This plan got the approval of prime minister of India in December 1953. The main area of this barrage for 15 kilometers of the western embankment and about 25 kilometers in the western embankment was in Nepal so the approval of Nepal government was also required. King Mahendra of Nepal gave the permission for this in April 1954. According to the plan 2.12 lakh hectare land in Saptari and Morang districts of Nepal and 24 lakh hectare land in Saharsa, Purnia and Darbhanga districts of Bihar would get irrigation facilities from this barrage. Along with this it was estimated that 20 thousand megawatts of electricity would be produced through this barrage.[i]

(Writer is an independent researcher)

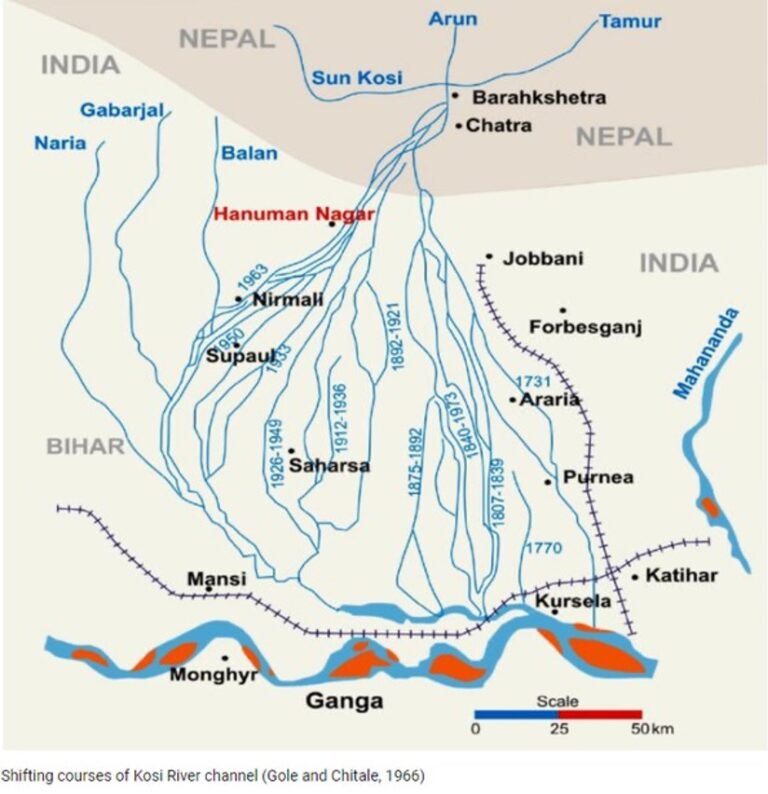

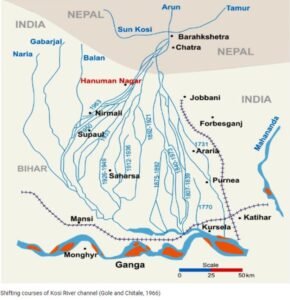

It must be noted how this river Kosi flowed and had changed course over the years, because the barrage was going to change the natural flow of river using a man-made barrage. Obviously, that was going to do some tweaking and tuning nature. At the times of Buknan (1809-10) Kosi ws flowing through Birpur and on its right side there was a minor stream named ‘Naliya’. A small river named ‘Barhati’ from Saptari district of Nepal came and met this stream. About 8 miles later this ‘Naliya’ merged into Kosi again. Dabhia subdivision of Purnia district was on the right bank of Kosi and onleft was Matiyari subdivision. One more river met Kosi in Sahebgunj, which was called ‘Ghaghi’ in the upper (northern) region and ‘Rajmohan’ in the lower (southern) region. Kusaha (Kushhar) used to be beside this ‘Ghaghi’ river. Today Naliya, Barhati and Ghaghi have been finished and people don’t even remember if these rivers existed. Kosi now flows through the barrage near Kusaha.

Construction of the Barrage

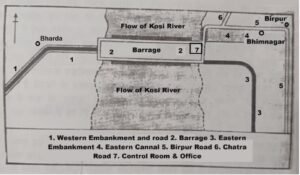

Once the central government approved the dam in December 1953 and Nepal government did the same in April 1954, the initial work for construction of barrage started on 14th of January 1955. For this purpose, 27-mile-long meter gauge railway tracks were build up to ‘Bathnaha’ (a small station in Purnia district) and 76 miles of roads were build up to Balua, Bhavanipur, Birpur, Bhimnagar, Chatra and Dharan. Once this initial work was completed King Mahendra of Nepal laid the foundation stone of Birpur barrage on 30 April 1959. Indian prime minister JL Nehru attended this event and in proximately four years the work of this barrage was completed. On 31 March 1963 this barrage turned Kosi in a new direction but this was formally inaugurated on 24 April 1965 by King Mahendra of Nepal, two years later.

(Map adapted from Havaldar Tripathi’s book on Rivers of Bihar)

The Treaties and the River

In the 220 years between 1730 and 1950, the river in Bihar moved around 115 kilometers to the west. During this process, regular flooding devastated an estimated 1,280 square kilometers in Nepal and 15,360 square kilometers in Bihar. British colonial engineers named the river Kosi “the Sorrow of Bihar” as a result. It was due to this frequent flooding that the British engineers contemplated two options: one to construct embankments on both sides of the river and the second was to build a high dam in the Barahchhetra gorge in Nepal. Later, after the Sugauli Treaty was sighned btween the Britishers and the Nepal Kingdom, East India Company started correspondence with Nepal on this matter in 1827. A four-member committee to study the nature of floods and measures for its control was formed through the Bengal Irrigation Department.

In 1891 the Britishers sought approval from the Nepal government to control the shifting course of the Kosi River. The Nepal Prime Minister, Bir Shamsher, agreed that this was a good idea and it wold provide protection against floods within Nepal too. In the May of same year, the Kosi area witnessed a major flood. The proposal never moved forward. At this point of time a canal was being built in Uttar Pradesh (then Central Provinces) using local knowledge and practices. To maintain this canal Rorkee College of Civil Engineering (later IIT, Rorkee) was developed in 1847. Somehow Britishers failed to appreciate the use of traditional knowledge systems in Bihar region and the embankments made by local Jamindars (landlords) were never appreciated. Till date even after annexing all such embankments, their maintenance is not anyone’s responsibility. Often, they break causing flooding in local areas.

To address the issues of floods, the Kolkata Flood Conference was held on 14 March 1897. Senior officials of the British government could not reach a definitive resolution on flood control of Kosi at that conference. Debates continued and forty years after the Kolkata conference, another flood conference was held in Patna in November 1937. During this conference LE Hall, former chief engineer of Bihar said that embankments shift the problem from one place to another. They do not effectively control floods. In the 1937 Patna Flood Conference, Jimut Bahan Sen, the then Secretary of Public Works and Irrigation for Bihar, presented the proposal for construction of a high dam at Barahachhetra.

Sir Claud Inglis, the director of Central Irrigation and Hydrodynamic Research Center of India, visited the Kosi are and in 1941 he gave a proposal to study various aspects of the Kosi River. By then the Second World War was going on and the proposal never gained any attention. After the visit of the then Viceroy Lord Wavell in 1945, Ayodhya Nath Khosla, Chairman of the Central Water and power Commission of India was assigned the responsibility of preparing the initial design for the dam at Barahachhetra. By this time the local population was getting fed up of the government apathy. At the same time the freedom movement of India was gaining traction and this resulted in a people’s conference on flood. In Nirmali of North Bihar a conference was organized by people on 16-17 November 1946. People demanded control of flow of the river, building a dam on the Kosi and through these they wanted electricity for every household. Next year on 06 April 1947 again a huge public conference of flood victims was organized in Nirmali.

The Searchlight Patna newspaper in its editorial of 21st July, 1948 edition wrote, “It is difficult to understand why the pangs and sufferings of the tormented humanity in living in the Kosi belt have not still forced the Government of India to treat the Kosi Project at par with the Damodar. Has not the realization dawned that the Kosi Problem will never be solved unless the dam is built? Here it is not a mere question of generating power but it is a question of saving the lives of human beings who are every year the silent victims of the flood scourge. Mute suffering never pays and here is an example.” Sardar Sarovar Project has displaced only 1,29,000 people-but the entire world knows about it. Here in Kosi, there are some eight-lakh people trapped inside of the embankment and as many outsides of it and Kamala area to it, and the number mounts up to twenty lakhs. They have been having a hell of a time, but no one cares a damn about them. Veteran leaders like Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Dr. Srikrishna Singh and Shri Guljarilal Nanda had participated in the Nirmali conference on 06 April 1947. The proposal of Kosi High Dam was mooted here publicly the very same day. But later on, embankments were constructed along Kosi instead of high dam.

Why the Dam was never Built?

High costs, lack of technical knowledge, relations with Nepal, and political considerations played a major role. For example, there was a competition between Punjab and Bihar over whether to build the Kosi High Dam or the Bhakra Nangal Dam in Himachal Pradesh. The Kosi High dam was far from Delhi and hence never chosen, the Nehru led government went ahead with the Bhakra Dam. Some historical documents do mention that Nepal needs to be consulted since Barahakshhetra was located in Nepal. The high dam in Nepal territory would benefit mainly Bihar (that’s in India). On 24 April 1954 Minister Gulzrilal Nanda went to Kathmandu to negotiate an agreement with Nepal. It was expected by the Indian team that the Nepal Prime Minister Matrika Prasad Koirala, who was leading the Nepal team in negotiations would sigh the treaty in a day or two.Years later in 1996 the government officials of Nepal and India discussed the Mahakali River Integrated Treaty and signed it. This took 42 years instead of two days, as was expected.

It is widely believed within Nepal that the country has not been able to secure its benefits with relation to India. India and Nepal have traditionally disagreed over the interpretation of the Sugauli Treaty signed in 1816 between the British East India Company and Nepal, which delimited the boundary along the Maha Kali River in Nepal. India and Nepal differ as to which stream constitutes the source of the river. The Sarada Treaty of 1920 was the first treaty signed between Nepal and India. Later the Kosi and Gandak Treaties were signed in 1954 and 1959. These led to the construction of huge dams. However, by 1980s Nepalese experts and then public started believing that the water treaties between India and Nepal were unequal. The larger state was giving few or no benefits to the smaller country. Here we have to keep in mind that even though the Tibet Autonomous Region in China occupies 3.08% of the Ganges basin, China is not considered in Ganges basin discussions by Nepal, India and Bangladesh.

Conclusion

Against this backdrop we have to think of ways to break the indefinite impasse and utilize the natural resources available to both the countries. On one hand where generating electricity through dams would create economic opportunities for Nepal to overcome the abject poverty, on the other, it benefits India too. Instead of responding to India’s proposals it might be better if Nepal comes up with its own plans on water resource development. With changing political atmosphere in Nepal, it would be beneficial for India to take up public relation exercises for betterment of its image in the minds of Nepalese citizen. We have to keep in mind the role of China in this region. It is an accepted fact that Nepalese political leaders have a negative attitude towards India. Efforts to win them over or bypass them can be made. All these measures need a continuous dialogue, which we can only hope to start in near future.

(Writer is an independent researcher)